Tags

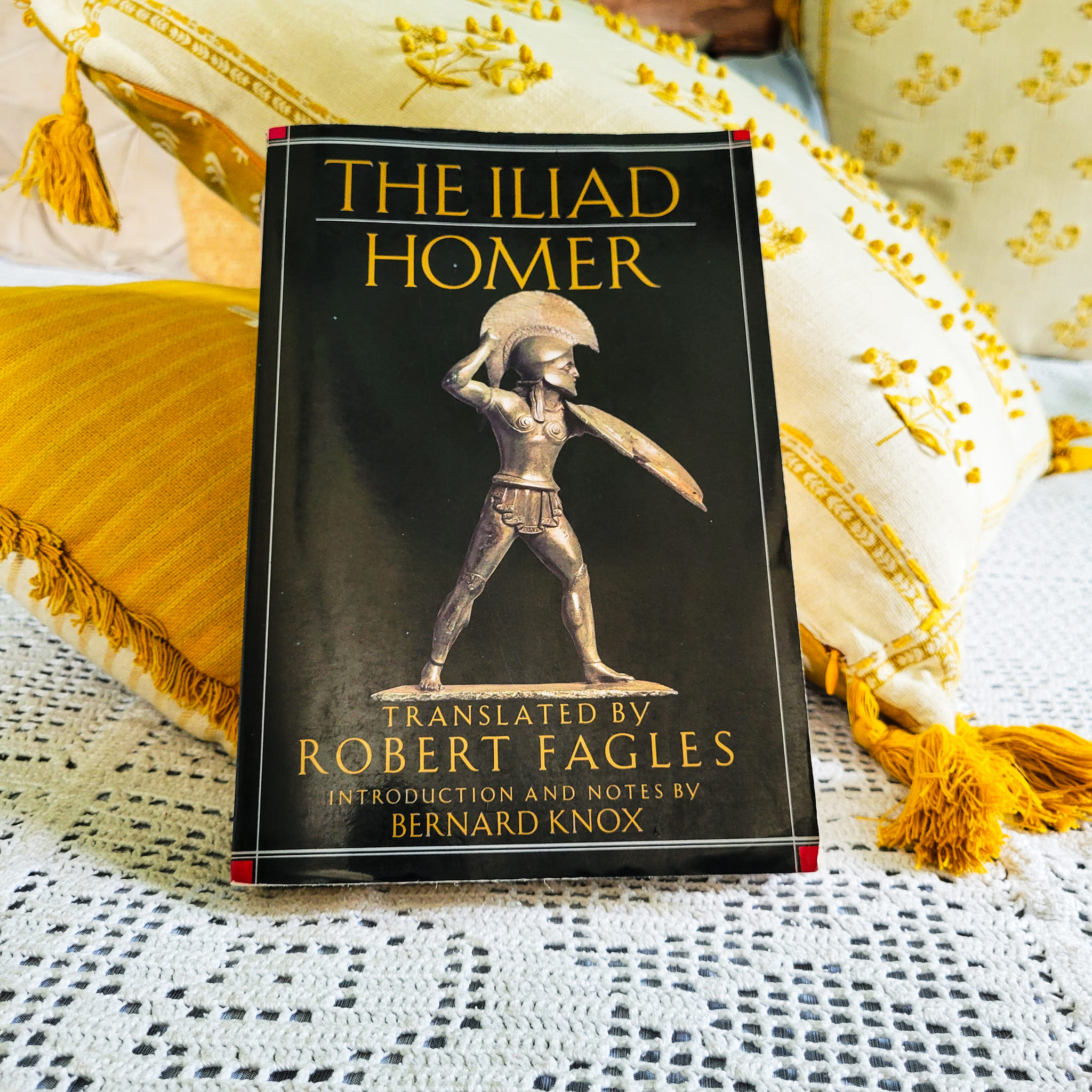

Books, Christian Classical Education, Christian Classical Homeschool, Classical Education, Classical Homeschool, Home Education, Homer, homeschooling, reading the classics, The Iliad

This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of these links, I may make a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting my blog!

This is a guest post from my good friend, Tabitha Alloway. We both have high schoolers this year, and they’re both going to read some Homer. While I’ve read The Iliad and The Odyssey recently so that I can be in conversation with my son about what he is reading, Tabitha has gone a step further and actually written out her thoughts, which I have found both interesting and helpful! I hope you will, too. Check out Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 if you haven’t already. Here’s Tabitha with Part 4:

“The Greeks seek after wisdom: But we preach Christ crucified… unto the Greeks foolishness” (see 1

Corinthians 1:17-31).

The Greeks had no shortage of bizarre and outlandish tales about their gods.

But Christ astonished them.

He died for mankind.

Their gods could not die—and certainly wouldn’t for anything so insignificant as a mortal.

He forgave man’s sins.

Their gods were quick to mete out justice and retribution, but slower to show mercy. Forgiveness was not a well-developed concept in Greek culture.

He conquered death.

A general resurrection of the dead? This was an outrageous thought—something beyond the Greeks’

wildest dreams. It just couldn’t be.

It was the teaching of the resurrection that divided the Greeks who heard Paul preach at Mars Hill. Some mocked. Others were willing to hear him again. A few believed.

To most, the gospel appeared weak and foolish. Their heroes smashed their enemies—they didn’t die for them! The Greeks could not understand a God who would suffer for mortals, just as the Jews, who were looking for a mighty conqueror to save them, did not recognize their humble Messiah who came to serve, rather than be served. And perhaps more than anything, the Greeks couldn’t fathom eternal life in immortal bodies—something they could only envy the gods for possessing. Or else, like Plato, found ridiculous and even undesirable.

Early Church Father Justin Martyr appealed to the Greeks’ understanding of the gods’ immortality to

explain the resurrection: “And when we say also that…Jesus Christ, our Teacher, was crucified and

died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propound nothing different from what you believe

regarding those whom you esteem sons of Jupiter [Zeus]” (1 Apol. 21).

The gospel was the power of God to salvation for everyone who believed, and God added both Jew and

Greek to his church, washing away strife, envy, wrath, and hatred through the Lamb who conquered sin, death, and the grave.

Christ is not only the Lamb of God. He is also the Lion of the Tribe of Judah. He did not suffer for suffering’s own sake; he did it for the joy set before him. He came to rescue a people for himself. He earned a name above every name. Glory. Honor.

In contrast to the Greeks, many today may be more comfortable with a God who is kind, forgiving, suffers without returning insult for insult, and mingles with the lowly, yet struggle with aspects of his justice that might not have been so difficult for the Greeks to understand.

A Servant who girds himself to wash his disciples’ feet is a comforting picture. Is he equally accepted as a King who will return to require worship—and destroy those who do not give it (Psalm 2)? A Lord who will rule with a rod of iron and smash his enemies to pieces (Revelation 2:27, 19:11-16)? A Lawgiver who will break the teeth of the wicked (Psalm 3:7/58:6-8)? An Avenger who “reserveth wrath for his enemies”

(Nahum 1:2) and is “angry with the wicked every day” (Psalm 7:11)? A God who tramples the wicked in fury until their blood is splattered all over his garments, and feeds their carcasses to the animals (see Isaiah 63:1-10, Revelation 19:11-18)?

“Kiss the son [signifying worship], lest he be angry, and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in him” (Psalm 2:12).

This picture of God may be a far less comfortable one for modern sensibilities, but it puts the cross into perspective. It tells us just how offensive we are to a righteous Sovereign.

Mercy only means something in the presence of true justice.

Christ came to reconcile us to God and deliver us from his anger. But the day of mercy will not last forever. When the door of the ark closes, only those found in Christ will be able to safely ride out the flood of

God’s wrath. Unlike the Greeks and their petty gods, God’s wrath is holy and justified.

The cross was not the end, but a means to an end: to redeem a people for God’s own glory and possession.

Both divine justice and mercy were displayed at the cross. God has linked our good and his glory together.

The God of the Bible is not about foregoing glory. We may be less comfortable with the concept of seeking personal glory (while in the pursuit of God’s glory) than the biblical writers are.

But Paul puts the idea of seeking glory, honor, and immortality for oneself in a good light (the full

context of Romans 1-5, of course, is an argument against trusting in works for salvation, and the need

to find it—this glory, honor, and immortality—by faith in the finished work of Christ). He motivates believers with the promise of glory, praise, and reward awaiting them, and warns them not to look for this from man on earth. (See John 5:44, Matthew 25:21, 23, 1 Corinthians 4:5, 2 Corinthians 10:17-18, Romans 2:6-7, 29, 8:16-17, 30, 2 Thessalonians 1:11-12, Galatians 1:10, Matthew 6:1-6 Colossians 3:23-24, James 1:12, Matthew 5:11-12, Ephesians 6:8, Hebrews 11:6, Revelation 22:12, 1 Corinthians 3:8-15, etc, etc.)

The question is not whether it is a moral thing to seek glory, honor, and immortality for oneself. That is

a given in Scripture. It is moral for God to seek his own glory, and it is moral for us to seek both his and our own (these are tied together for the Christian). But how and where are we looking to find it? Vainglory is empty, vapid, invaluable. It is the kind of glory most men seek, and it falls far short of the glory awaiting the believer.

C. S. Lewis wrote in The Weight of Glory,

“When I began to look into this matter I was shocked to find such different Christians…taking heavenly

glory quite frankly in the sense of fame or good report. But not fame conferred by our fellow creatures

—fame with God or (I might say) ‘appreciation’ by God. And then, when I had thought it over, I saw that this view was scriptural; nothing can eliminate from the parable the divine accolade, ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant’.”

Striving for reward is a concept that would have been very familiar to the Greeks. In fact, Paul uses the

picture of running for a prize or competing in athletic games to illustrate the Christian life (1 Corinthians 9:24-27, Hebrews 12:1-3, Philippians 3:13-14, 2 Timothy 4:7-8). Earning prizes and glory is something his Gentile audience would have easily understood.

So there are aspects of our God that the Greeks probably could have understood, to some degree, even better than we might today. And yet, he was still so different from their own gods, from anything they had conceived in their own minds.

They may have been able to appreciate God’s demand for worship and his promise of personal glory and reward for his followers. But the idea of taking up one’s cross and being willing to relinquish temporal life to save one’s eternal soul (Matthew 16:24-25) might have been less tasteful.

They might have been able to identify with Christ as a conquering King and hero. But His life as a suffering Servant to mortals would have been more difficult to understand.

They may have been able to recognize a God of justice. But a God of mercy and forgiveness who reached out in love to those who were his enemies would have been harder to comprehend.

“Among the gods there is none like unto thee, O Lord, neither are there any works like unto thy works… thou art God alone” (Psalm 86:8, 10).

The Greeks valued glory, honor, wisdom, and longingly wished for immortality, a resurrection of the body. Those among them who believed found all these things in Christ—and more. They were freed from wrath, pride, envy, and the sins that so easily beset men. Finding peace with God, they experienced it with their fellow man and strife was “able to die”—a thing Achilles fruitlessly sighed for. They became heirs of a lively hope, an inheritance incorruptible and undefiled. They enjoyed the hospitality and fellowship of the house of God.

While the gospel appeared foolish to the rest of their countrymen, to those who believed, Christ was

made the wisdom and power of God… a power not even their greatest heroes could boast.

More in this series:

Reflections on The Iliad, Part 1: “Rage”

Reflections on The Iliad, Part 2: Humanity and Hospitality

Reflections on The Iliad, Part 3: Some Thoughts on Greek Thought

Other posts with Tabitha:

No Story is the Same, No Pain Ever Wasted

Introducing the Living Books Consortium